Having lived in the city all my life and not being a skier or an experienced hiker, I’ve mainly observed the Snowy Mountains and the Kosciuszko National Park from a car. I’ve admired the worn mountain tops, the craggy rockfaces and the running stream of the upper reaches of the Murray River.

I knew that the sources of the Murray, Murrumbidgee and Snowy rivers are found in the Snowy Mountains. But I didn’t know that this alpine high country is a sponge that holds and then releases water into the river system that eventually finds its way down from these the lands of the Ngarigo people to the lands, known as the Coorong, of the Ngarrindjeri people.

Last time we drove through the Park, we were shocked at the numbers of feral horses. They seemed to have exploded since we last visited. I know now that our impressions were correct: the population of horses had indeed grown by thousands. I’ve now also seen at close quarters how the hooves of the horses are literally tearing apart the delicate mosses that form a cover for the sponge. What might look like low-grassed paddocks from a distance are actually part of a delicate fragile Alpine ecosystem made up of mosses, snow grasses and daises. This ecosystem is Eastern Australia’s life blood.

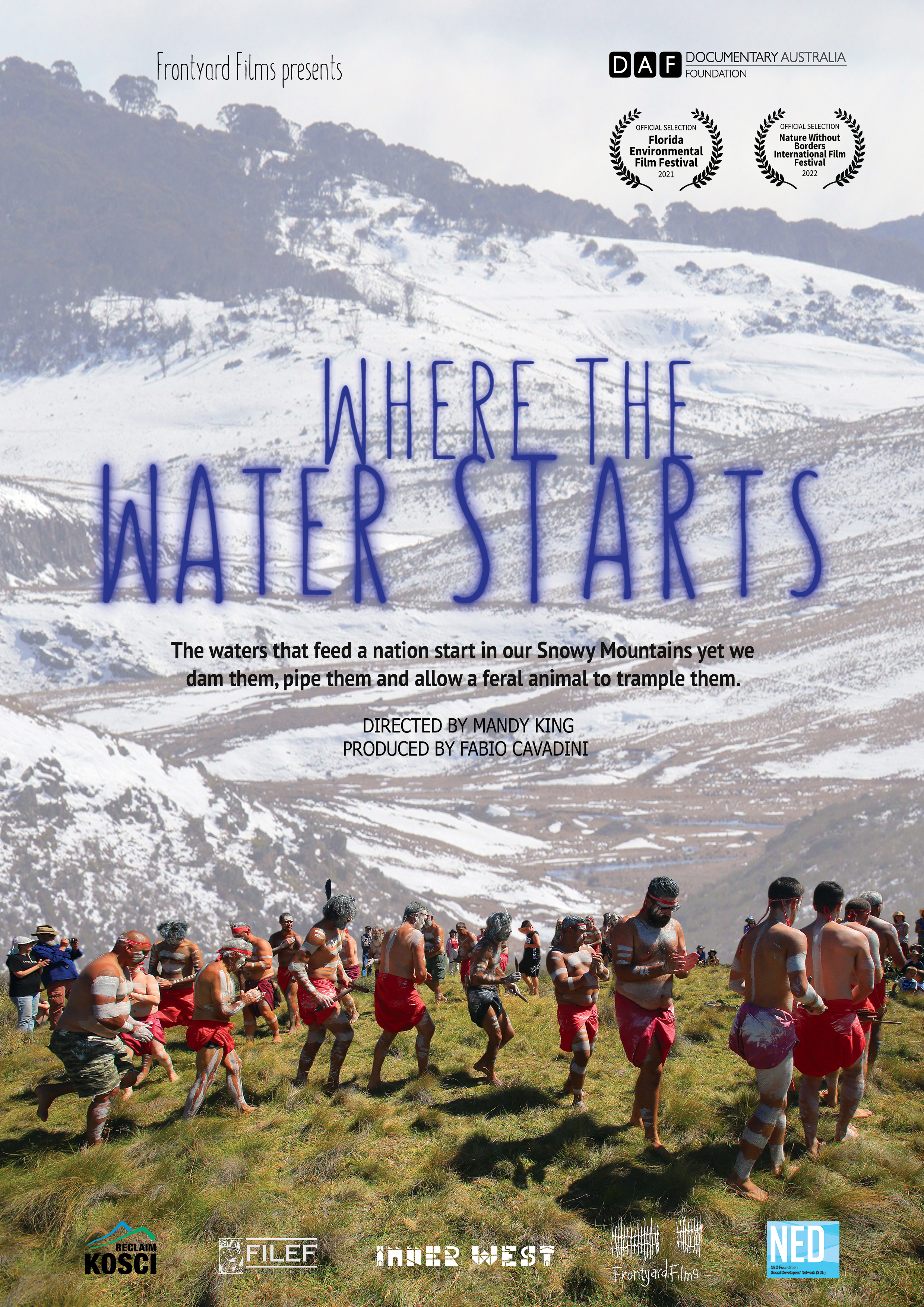

I became aware of these things when I watched a preview of Where the Water Starts, the latest documentary by Frontyard films, which is a partnership between Director Mandy King and Fabio Cavadini, her co-Producer and Cinematographer. Since the 1980s, King and Cavadini have been making documentaries about Australia and the Pacific in a style that combines interviews with contemporary and archival footage.

Where the Water Starts will have its virtual launch this Thursday October 28th with a Q & A with the filmmakers and others to follow. The launch event, which is hosted by Frontyard Films and Reclaim Kosci, comes at a crucial time in the fight to save the Kosciuszko National Park.

At the heart of this film is the demand from Indigenous people with thousands of years of connection to the area to have a strong say in how the park should be managed. It begins with a gathering for a smoking ceremony and dance of Indigenous people and supporters from across the country that draws life from the rivers that rise in the Snowy Mountains. We meet Yuin Uncle Max Dulumunmun Harrison who tells us, “it’s about our land being desecrated and it’s still being desecrated. It’s about the Snowy Mountains, Mount Kosciuszko - the biggest sponge in the country that holds the water and then releases it through a lot of great rivers.” Uncle Max hits the clapping sticks in the four directions along which the rivers flow.

Wiradjuri Elder Aunty Sue Bulger, CEO of the Brungle Tumut Local Aboriginal Lands Council, explains that she was born on the banks of the Murrumbidgee River near Gundagai. She also has Walgalu and Ngunnawal heritage. She has visited the spring at the river’s source and witnessed the damage to what she says “essentially is the birth of a river”. She explains that she has brought leaves to the ceremony to remind her of the country of her parents who are with her in spirit.

Uncle Max explains that the gathering - Narjong - was suggested by Richard Swain - “we call him ‘Cooma’” -a key figure in the struggle and the film. Swain has been an alpine river guide for 25 years. He is partly descended from the Dabee clan of the Wiradjuri people. His parents moved to the area before he was born and he was introduced to this country by his grandfather who taught him about “the tucker and water and etiquette”. He remembers that “there were more birds when I was a kid and more frogs.” His grandfather told him that the history of people not caring for the land was a short one.

Swain still takes tourists on canoe trips into remote parts of the river but at a certain point, he decided that he could no longer promote the idea of a pristine environment when it was being turned into a ‘feral animal environment’. These days he is an Indigenous Ambassador for the Invasive Species Council. His partner Alison is a campaigner for Reclaim Kosci, a contributing partner in the film.

The Indigenous elders are not anti-horse, but do not want brumbies to be allowed to destroy the park at the expense of the broader environment. Ngarigo Elder Aunty Rhonda Casey tells of riding her pony in the area as a child and if “I went anywhere near the springs I would be in a lot of trouble. You couldn’t go there. You would sink up to your hip.” The country is very “bony country. It has extreme seasons. It’s not a horse paddock. It’s not improved pasture.” Her heritage also goes back to early cattle grazing families but she does not think the white colonial approach is compatible with the survival of the Park.

Climate change, which has already brought increased drought and catastrophic fire, is a backdrop in the film. As the film was being made, the 2019 fires burnt through huge swathes of the bush. Heat, fires and drought are all predicted by climate scientists to increase. Since 1954, the depth and duration of the snowpack in the Kosciuszko region have declined. Rising temperatures are a problem because the alpine species already at their distributional limits in the fairly low Australian Alps have nowhere else to go. If the tree line rises, woody shrubs may expand into grasslands and herb fields. Unfortunately, as Swain observes, the tree line has already visibly shifted

While the connection between Indigenous people and the land is at the heart of the film, the spirit is also one of a partnership between Indigenous people, other community groups and scientists working together in order to conserve the Park and rehabilitate degraded areas.

“Whose responsibility is that to take care of our wildlife and our environment and the planet that we live on? It is our responsibility, it is your responsibility, it’s everyone’s responsibility”. (Uncle Bruce Shillingsworth)

Richard Swain, Ngarrindjeri Elder Uncle Moogy Sumner and Yuin Elder Uncle Max Dulumunmun Harrison at ‘Narjong’.

The filmmakers’ approach is to present a case for the protection of the Park rather than to weigh up different points of view about how the National Park should be managed. The underlying argument is that the perspective of ‘caring for country’ that is embedded in Indigenous understanding and history aligns with the findings of scientists. I agree with this approach – if the scientific findings are solid as they appear to be, to do otherwise is to present a ‘false balance’ in the same way as has too often occurred in reporting of climate change. ( You can find more about my research on climate change reporting here.)

The film also does not reduce threats to Kosciuszko to just one or two environmental factors. A patchwork of factors are interacting to threaten the park. Ex Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s pet project Snowy Hydro 2 is also causing even more disastrous damage to the Park. Entrenched political and economic interests are at stake.

Watching the film stimulated me to do a little more research. In 2018, recently resigned Deputy Premier and National Party MP for Monaro John Barilaro introduced his Kosciuszko Wild Horses Heritage Bill. He listed it as one of his achievements in his resignation statement.The object of the bill was to recognise the cultural heritage value of wild horses and to provide for their protection and preservation in the park. The bill was based on the assumption that preserving wild horses in the park is sustainable. It ignored the findings of scientists who have repeatedly rejected this assumption. When he introduced his Bill, Barilaro made much of the community panel that would provide input for a management plan for the feral horses. He chose to celebrate a single member of the community, his close ally and former member for Monaro, Peter Cochran. Cochran, after years of campaigning in favour of brumbies, was closely involved in producing the bill that overrode the Kosciuszko National Park Plan of Management. He also donated to Barilaro’s political campaign.

The film explores how the pro-brumby case has weaponised old colonial myths about the role of the male stockman in shaping Australia. Although these myths have been contested for at least half a century, such tropes have had a resurgence with the rise of nationalist right wing politics since the 1990s. It is disappointing but not surprising that Richard Swain and others have been subject to threats and racist abuse that is just as unacceptable in environmental politics as it is on the football field.

As one member of the broader community ignored by Barilaro, I was annoyed to discover when the Reclaim Kosci campaign applied under NSW’s Freedom of Information law, the GIPA act, to view the minutes and other documents relevant to the panel, they encountered a high level of secrecy. When eventually, the group managed to obtain some of the Community Panel minutes they were heavily redacted. Just as alarmingly the scientific panel minutes contained over more than 90 pages of blacked out material. The limited amount of material revealed suggested that some of the scientific advice that the protection of Indigenous cultural values should be incorporated into the management plan had been ignored by the NSW government.

The draft horse management report was finally released on October 1 this year. There is now a consultation period until November 1. If you care about the ecological future of the park rather than promoting shortsighted colonial myths, you will not be satisfied with the plan. There are now approximately 10,000 horses in the Park. The plan does promise to clear horses from some sections of the Park but to leave them on more than a third of the park. This would mean about 3000 horses. Because feral horses are not compatible with the natural ecosystem, environmental damage in those sections will become permanent. By prioritising the desires of humans who want to celebrate brumbies, the rights of Indigenous people to their lands and the ecosystems that form them are jeopardised. Some argue that the 23 threatened native plant species and 11 threatened native animal species also have a right to exist.

Each of us is faced with a myriad of critical climate change and other ecological threats in both our local, regional and global environments. It’s hard to keep up with them all, let alone commit to combatting them. But having watched Where the water starts, I grasp the urgency of this issue and the consequences for us all if we sacrifice the Snowy Rivers ecosystem to feral animals. Like threats to the survival of the Great Barrier Reef, they are a threat to all of us.

If like me you were not on top of this issue, there could be no better way to catch up with it than to watch the film at its virtual launch and hear about the latest developments from the filmmakers and other experts in the Q & A afterwards. If you are already involved, you won’t want to miss it. John Barilaro may be gone but his so-called achievements still threaten us all. Four scientists recently argued in The Conversation that Barilaro’s retirement offers “an 11th-hour chance to safeguard this significant national park”.They wrote,”Feral horses trample endangered plant communities, destroy threatened species’ habitat and damage Aboriginal cultural heritage — all the while increasing in numbers. The draft plan would keep many horses in the national park, locking in ongoing environmental and cultural degradation”. One of them David Watson. Professor of Ecology at Charles Sturt University, will be on the panel after the film launch.

Where the Water Starts was funded by Documentary Australia Foundation, the Inner West Council Individual Artists program. the NED The Social Developers’ Network and hundreds of individual donors including the author.

The Q and A session after the launch will be chaired by environmental lawyer Sue Higginson who was previously the CEO of the Environmental Defenders’ Officer.

If you want to make a submission, there is a full guide here.